MRS 2020 #1: Active learning and automated materials science

tags: [dft mrs machine_learning Automation of materials discovery and robotic labs has had a big year, for a nice overview there is an article in Nature covering many recent breakthroughs. This popularity is reflected in a lot of exciting talks at MRS on the topic of automated labs, I’ll very quickly cover background on one of the most important enabling methods for automated labs, that is active learning, and then give a pick of three talks that really caught my attention.1

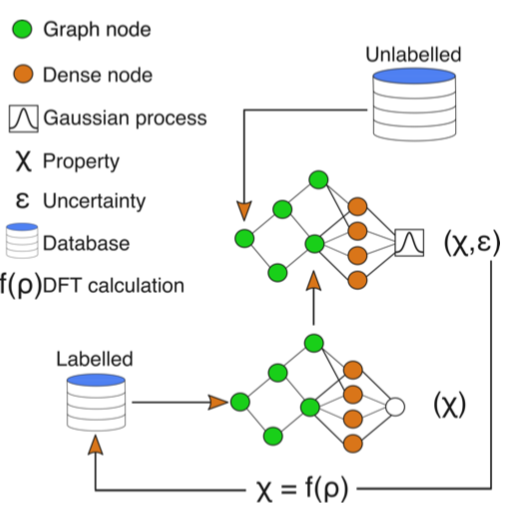

Active learning (AL) is a sub-field of machine learning (ML) where the ML algorithm actively requests the next set of data for its training. Supervised ML works by learning a relationship between some input and a set of labels associated with the input. The labelled inputs are the training data. Often the labelling of these inputs (e.g. diffraction patterns, molecular structures, micrographs) is the most demanding part of the process of training the algorithm. So we would really like to choose to label those inputs that will improve the performance of the algorithm the most. To decide this it is useful to know how much a new, un-labelled input is “like” the other inputs that are already labelled. When we know this we can define an “acquisition function” that decides which un-labelled data to label for the next round. In practice there is an explore-exploit balance in this acquisition, do we want to label more points close to an existing good point and make a specific but accurate model for that area, or do we want to label inputs that are very different to the existing inputs, thereby building a more general model which is perhaps less accurate in a specific region. But once we have defined the acquisition function we can essentially perform a “closed loop” experiment. The ML model trains on existing data, then looks at the un-labelled inputs and decides which ones to label, these are automatically labelled (e.g. a robot does an experiment, or a computer runs a DFT simulation) and the model is then retrained. The loop continues until some specific target is achieved, where the results of the experiment have now been optimised controlled by the ML model.

The three talks I picked from many on this topic cover a diverse range of applications, additive layer manufacturing, crystal synthesis and electron microscopy.

Keith Brown from Boston University talked about the work they did to use AL to optimise the toughness (a non-linear materials property) using AL with additive manufacturing. He also had a nice discussion about the scenarios in which AL is really useful for materials science.

- The talk is here: https://2020mrs.cd.pathable.com/meetings/virtual/gefEqoLT224ug4Jt3

- An associated paper is here: https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/6/15/eaaz1708

Joshua Schrier presented his groups work on AL for discovering optimal synthesis conditions for hybrid halide perovskites. There was also the interesting application of meta learning to make sure that the models generalise better.

- The talk is here: https://2020mrs.cd.pathable.com/meetings/virtual/FcGABBe7HrFDTWA9g

- An associated paper here: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c01153

Sergei Kalinin gave a whirlwind overview of some of they work they are doing at Oak Ridge to build automated electron microscopes - I need a good acquisition function to choose from the arXiv codes associated with the numerous interesting studies they have done. It was particularly nice to see a materials scientist responding to Judea Pearl’s causal inference and do calculus. They use the tools of the do calculus to tease out the causation and correlation between local and global order in phase transitions observed in an electron microscope.

- The talk is here: https://2020mrs.cd.pathable.com/meetings/virtual/5zznFinwB2x7ydTLW

- Associated papers:

-

I obviously missed a bunch of really interesting talks, this is by no means exhaustive. ↩