Hydrogen bonding in hybrids

tags: [dft hybrid_halides research hybrids I explore how our new work sheds light on how hydrogen bonding controls the properties of hybrid organic-inorganic perovskite materials. The full paper was published late 2017 in The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, it’s free open access and you can find it here.

A lot of the work that I have been doing in recent years concerns hybrid materials, which combine building blocks from the traditionally separate fields of organic and inorganic chemistry. This is a very interesting area to work in as it involves a confluence of ideas, methods and languages, making it fertile territory for new advances. I think that our recent work on hydrogen bonding strength in hybrid perovskite materials is a good example of this.

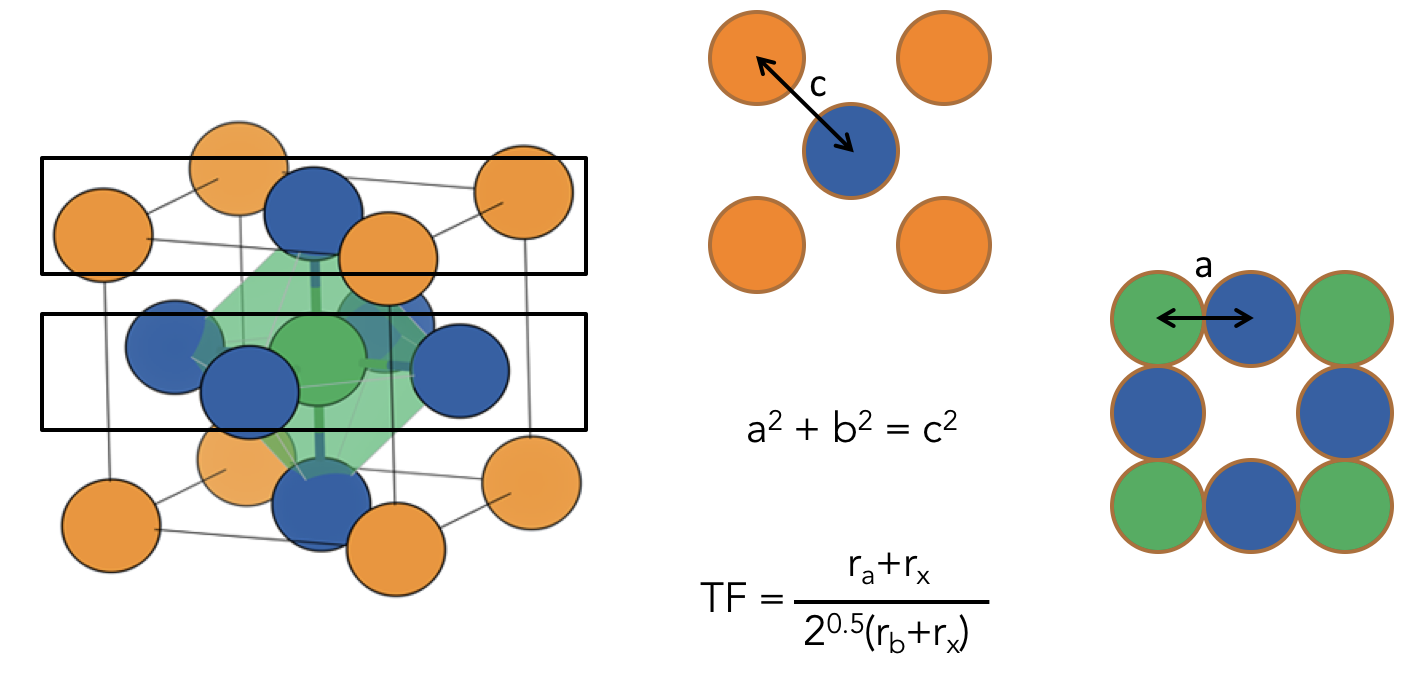

Perovskites are a good place to start as they are almost the archetype of classic design principles in inorganic solid state chemistry. The rules of Goldschmidt are amongst the most celebrated composition structure relationships, that is a way to relate the elements in a chemical formula to the 3D arrangement of the atoms in a solid. Goldschmidt built a beautifully simple geometric representation of the perovskite lattice and essentially represented the problem as one of packing spheres of different sizes (various elements). See the Figure below.

The interesting development in recent years is that people have started to replace the solid atomic building blocks of Goldschmidt with organic molecules. Hence we have a meeting of organic and inorganic chemistry in a whole new class of materials. I won’t go too much into how great dense hybrid materials are, but for more on this, there’s a nice article “There’s room in the middle”, by Tony Cheetham and C.N.R. Rao, two of the pioneers of the field.

In the field of organic solids there are a whole bunch of different forces at play. One of the most important is hydrogen bonding. As chemists know well, hydrogen bonds are not as strong as classic covalent or ionic bonds, but can play a huge role in materials properties. The most well known example being, of course, water.

Now it is clear that hydrogen bonding is going to play a big role in these hybrids too. If we could know how strong hydrogen bonding was going to be we could predict all sorts of interesting properties, such as the temperature at which the molecules start to rotate, known as the order-disorder transition, which is important in applications like ferroelectrics and magnetics.

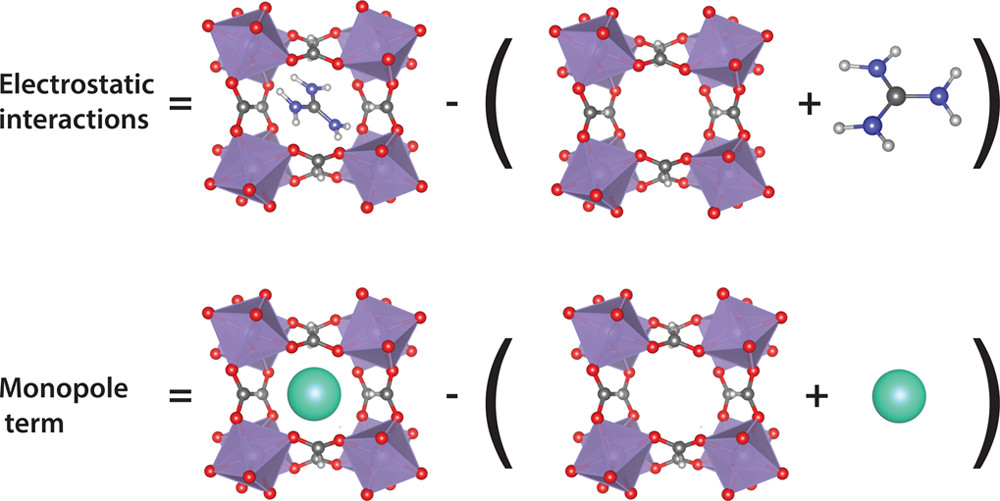

The problem is, that it is very difficult to deconvolute the different contributions to the overall lattice energy to separate contributions. Actually, Tony Cheetham’s group did some work to estimate hydrogen bond strengths using quantum mechanical calculations. Their approach was to calculate the energy of the crystal ($E_{hyb}$), then to remove the organic molecule and recalculate the energy without the molecule ($E_{ino}$) and the energy of the molecule alone ($E_{or}$), then the difference $E_{hyb}$ - ($E_{or}$ + $E_{ino}$) is the molecule-inorganic interaction energy. This approach is fine and formally correct, the problem, if we want hydrogen bond strength, is that this energy difference is actually dominated by the ionic interaction between the charged molecule and inorganic framework.

This is where our new approach comes in. Building on the approach outlined above, we now introduce a second system, with an inorganic ion (of equal charge) replacing the organic molecule. We then calculate the energy difference as above, and also the identical energy difference of the fully inorganic system. Since the inorganic system has no hydrogen bonds, but does have the ionic interactions, the difference in the differences is now the hydrogen bond strength. The scheme is represented in the figure below.

We compared our calculated hydrogen bond strengths to experimental evidence for bond strength from solid-state NMR measurements. We were then able to match the calculated hydrogen bonding strengths of a range of hybrid perovskites featuring formate molecules to the order-disorder transition temperatures. This kind of validation gives us confidence in our approach, and means that we can use the method in the future to design new hybrid materials, applying computational screening to identify promising targets, before undertaking complicated synthesis. What’s more, we hope to use these approaches to help establish new sets of design principles to augment the successful approaches from the separate fields of organic and inorganic chemistry, pushing this new field forwards towards true rational design.